Looking Deeper into the Problems with Covenant Theology (3)

2. CT starts its reading of the Bible in the wrong place.

In Part Two of this series I said that for CT’s having the NT to interpret the OT is like the introduction of color televisions to replace the old black and white screens. Whereas for people like myself it is better compared to a deconstructionist interpretation of a classic novel which all but ignores what the novel says and its way of saying it.

Some may think that the second comparison is unfair. I do not want to be unfair so I shall need to elaborate a bit. I have pinpointed the way CT’s view the Bible Story as a history of redemption. That is what it is all about. Certainly, redemption is a very important part of what the Bible is about, but it is not the whole story. There is, for example, a major theme that transcends the problem of human sin and that is the “cosmic drama” being played out between God and Satan, and between God’s plans and Satan’s plans. Not that this is an equal conflict. If God was not upholding Satan and his demons in existence from moment to moment they would cease to exist (Heb. 1:3). And of course, that would also be true of every other being or thing in creation. But this conflict does not of itself have anything to do with redemption. Satan and his host are not to be redeemed. They are to be judged.

Another important theme is the creation itself, blighted not only by sin but also by the curse that the Lord uttered over it. While I agree that redemption overlaps with this theme because man’s salvation will impact earth’s transformation and creation’s eventual freedom from the curse (in the new heavens and new earth), it is also true that the cosmos, however one conceives of it, as well as the spiritual realm, was designed for Jesus Christ to rule over for God the Father. Hence, this created realm has its own intrinsic value and purpose – creation is an unfinished project.

Now it is easy to see how interconnected all this is. But still, if one is going to see the whole of the Bible’s storyline it is critical to “pan-out” far enough to get everything in. And centering on redemption-history is just not a wide enough angle. Important considerations get left out. Furthermore, the history of redemption lens fosters an attitude man-centeredness because it looks at things from our perspective. On the other hand, once we “pan out” to include the cosmic drama and the creation project (of which the former is part of the latter), things become more God-centered.

When reading any book it is not a good idea to start two-thirds in. Along with this reduction of the Big Story to redemption-history comes a hermeneutic which stems from the cross. The problem I see with this is that it pre-determines outcomes. For one thing, the cross occurred at the first coming, and therefore those who begin at Calvary tend to interpret biblical prophecy from a first advent vantage-point. When this happens it is a foregone conclusion that any prophecies which don’t fit the first coming (other than the very clearest second coming passages) must be made to fit the first coming. Whole swathes of OT prophecy will have to be reinterpreted and transformed to be “fulfilled” in Christ and the Church.

A knock-on effect of this will be the revision of what it means to be a prophet. Instead of being a foreteller prophets are turned into moral preachers to their contemporaries. Again, there is some truth to the forth-teller description, but that is not what defines a prophet; a prophet is defined as one who speaks for God about the future (Deut. 18:21-22; Amos 3:7). This test of a prophet is all but forgotten among those who hold a first coming hermeneutic.

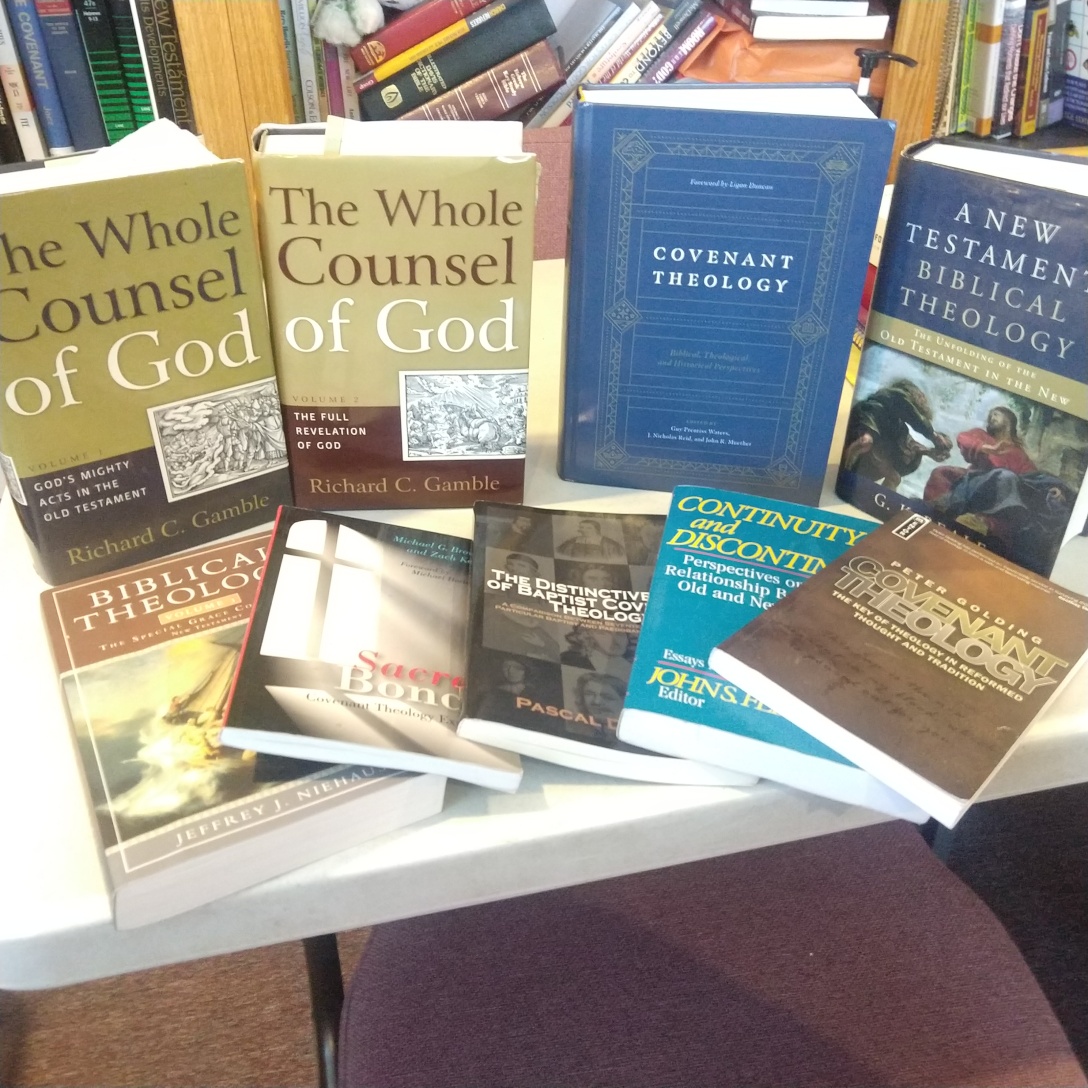

Another casualty of CT hermeneutics is progressive revelation. For CT the “progress” isn’t really trackable back into the OT, at least not without a truckload of typological gymnastics, which, coincidentally, mainly finds fulfillment at the first coming! In CT (as well as NCT) typology is the essential tool which makes the covenants oaths of God amenable to being understood from the foot of the cross. A more suitable moniker for progressive revelation as dished up by CT is “supercessive revelation,” since the plain meaning of earlier texts gets replaced by new meanings further on. This is because, as I have said before, in CT (and NCT) progressive revelation “only refers at best to the completed revelation, but not the process of revelation.” Consider this statement from G. K. Beale:

“Perhaps one of the most striking features of Jesus’ kingdom is that it appears not to be the kind of kingdom prophesied in the OT and expected by Judaism” – A New Testament Biblical Theology, 431 (my emphasis),

This statement can only be made if revelation is not progressive but supercessive. If all the steps towards fulfillment can be transformed out of recognition right at the end then “progressive” is simply the wrong word to use. Only if the plain meaning is maintained all along the line of progress does the adjective apply.

Then there is the influence of the approach upon NT prophecy, especially when NT passages begin to look like they are picking up on OT covenants and interpreting them literally. Redemptive-historical hermeneutics, which is first coming hermeneutics, cannot allow this. This means that the Olivet Discourse, or the Olive Tree metaphor in Romans 11, or the mention of the twelve tribes in Matthew 19:28 or Acts 26:7, or Revelation 21:12 must undergo corrective hermeneutical surgery. Also going under the knife will be mentions of a future temple in Matthew 24 or 2 Thessalonians 2 or Revelation 11. In fact, the entire Book of Revelation must have radical plastic surgery to look like a first coming book and not a second coming book.

Finally, a redemptive framework which circles around the cross and resurrection will tempt the interpreter to neglect what was promised in the OT, particularly to the nation of Israel, and it will blunt the force of the covenant promises that God must deliver on which were sworn before Calvary, and it will treat the NT Church is if it were the promised Kingdom which the prophets envisaged.

If we return to my illustrations for a minute, CT’s believe the transformations of OT covenants and prophecies into “fulfillments” which no OT believer could have dreamed up are like the introduction of color TV’s when people were used to black and white pictures. People like myself though believe that this transmogrifying of the prophets is what is demanded by Covenant Theology, not what is demanded by the inspired writers. Hence, it is more like tampering with what the Book is actually saying and not at all like switching to color.

This entire installment is extremely well-put, but especially liked:

if one is going to see the whole of the Bible’s storyline it is critical to “pan-out” far enough to get everything in. And centering on redemption-history is just not a wide enough angle. Important considerations get left out. Furthermore, the history of redemption lens fosters an attitude man-centeredness because it looks at things from our perspective. On the other hand, once we “pan out” to include the cosmic drama and the creation project (of which the former is part of the latter), things become more God-centered.

CTs might be surprised to hear someone express the view that CT’s interpretive lens more man-centered than a truly wholistic hermeneutic which allows separate threads of God’s work to speak on their own, but in fact this is the case.

Excellent stuff!